How visual brand affects user experience

How visual brand affects user experience

You don’t need the full graphical elements to recognize a familiar environment.

Some graphical desktops have a background image or other element that is so recognizable, it just stands out. For example, when Microsoft released Windows XP in 2001, they included a desktop “wallpaper” image of a grassy field and happy clouds that became so recognizable it became iconic.

But it’s not just images that define a visual identity for a graphical desktop. The shapes and arrangements of elements in the presentation also define the graphical desktop’s “brand.” Because of this, we associate the placement of certain elements with a particular identity.

A few years ago, I considered the visual brand or visual identity of graphical desktops, and I wondered if I could break down the components of a desktop to just its most significant elements that users would recognize.

Basic shapes

One interesting reference for how we infer meaning to simple shapes is the book Picture This by Molly Bang. This is a must-read book for anyone who is interested in user interface design, because Bang’s book demonstrates how we perceive different shapes in different ways, and how we might interpret a new meaning or emotional change by altering the placement or color and arrangement of those shapes.

Our recognition of user interfaces works with the same association. Even without the distinctive wallpaper background, we can recognize certain arrangements of user interface elements based on their shapes and colors. By altering the arrangement of these shapes, or changing their colors, we can represent a new user interface.

A sample of user interfaces

Let’s try an experiment to demonstrate how to represent certain familiar user interfaces using simple blocks of color. Can you guess which operating systems are shown here?

In no particular order, the operating systems shown above are:

- GNOME (current)

- GNOME 2

- Microsoft Windows (current)

- Microsoft Windows XP

- Microsoft Windows 3

- MacOS (current)

- MacOS 9 (or any older MacOS)

- the command line (Linux, Unix, DOS)

Even without icons or logos, you can probably make good guesses for many of these.

The GNOME desktop

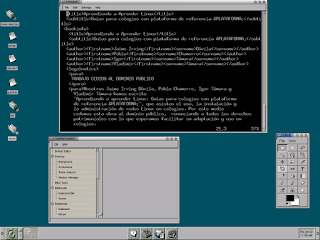

GNOME has a distinctive look, so let’s start with this graphical desktop. GNOME started in 1997 as an open source alternative to other graphical interfaces for Linux. Before GNOME, Linux didn’t have a true “desktop,” but instead used window managers to simulate the functionality of a true integrated desktop environment. GNOME 1 used a visual framework similar to Microsoft’s Windows 95, which was the most popular graphical desktop for PCs. The gray task bar at the bottom of the screen was immediately familiar to many users in 1997:

GNOME 2 (2002) modified the user interface arrangement, placing a separate task bar at the top where users could launch programs, and where GNOME displayed the date and time. A separate task bar at the bottom of the screen showed running applications. This arrangement neatly represented “things you can do” (top) and “things you are doing” (bottom).

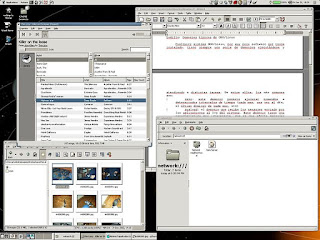

GNOME 3 (2011) completely redesigned the user interface. In response to some user frustration about navigating windows and launching new applications, GNOME 3 removed the traditional task bar in favor of an “Overview” mode that showed all running applications. Instead of a “Start” menu, users clicked on an “Activities” button, which entered “Overview” by default. At the top of the screen, GNOME used a solid black bar, with “Activities” on the left, time and date centered, and system status indicators on the right.

User interfaces with shapes

The visual brand of a graphical desktop has strong ties to its identity. Colors, fonts, placement of user interface elements, and window decorations are just some of the ways that user interfaces distinguish themselves.

How many of the mockups were you able to associate with a desktop environment? Here is my association for each:

MacOS

Apple changed desktop computing in 1984 with the release of the Macintosh computer. The MacOS interface sported a simple menu bar at the top, which was shared between applications. While MacOS added other elements in later versions, including a shortcut “dock” at the bottom of the screen, the menu bar has remained an iconic user interface element.

Windows

Microsoft’s first entry to Windows was buggy and lacked the ability to overlap windows, but later versions became a popular addition to PCs in the home and office. Windows 1, 2, and 3 used a simple window decoration. Windows 95, Windows 98, Windows XP and all later versions used a “task bar” at the bottom of the screen, with a “Start” button to launch applications.

GNOME

GNOME 1 borrowed certain elements from the Windows interface, while GNOME 2 significantly deviated with its two-bar approach. GNOME 3 changed the interface entirely, using a single top bar not unlike MacOS, but themed in black with white text.

Command line

Computer users have navigated using a command line interface for as long as computers have sported some kind of terminal and keyboard input. While the features of the command line experience are distinct to each operating system, the general appearance of a prompt on a black screen is universal.